Whether ensuring working conditions are safe or detecting employees’ elevated temperatures, thermal detection is increasingly important in the workplace.

It’s a quirk that leaves many scratching their heads – the fact that while minimum temperatures exist to protect workers (16°C or 13°C if work involves vigorous effort in the UK), there is no legislation that sets any maximum temperatures people can reasonably be expected to work in.

With the UK Health and Safety Executive (HSE) simply advising employers to consider the impact of six main factors – air movement, air temperature, humidity, clothing, metabolic heat and proximity to objects radiating heat – legislation has long been regarded as inadequate.

As Douglas Cameron, head of safety services at Law At Work, says: ‘By saying employers must “by process of risk assessment alleviate environmental conditions”, it doesn’t even say firms must cut ambient temperatures. It’s just that they need to work around it – say by putting in fans to increase air movement or by giving people additional breaks.’

And yet, despite this lack of clarity, the impacts of not addressing what’s sometimes called ‘thermal comfort’ can be severe – everything from inability to concentrate and fatigue, to nausea, headaches, confusion, exhaustion or even heat stroke. It’s why kitchen workers and those in other hot environments have long campaigned for better rules.

THERMAL WORK LIMITS

One issue with temperature is that some people aren’t impacted at all, but for others, it can be debilitating. This makes creating adjustments for it difficult. While there is the concept of a thermal work limit – laid out in ISO 7933 – its use is not widespread, and it still applies to those regarded as ‘acclimatised’ to hot temperatures – one of the aspects that determines a person’s ability to cope. Heat susceptibility is also impacted by age, general health, weight and hydration levels.

Thermal detection technology has long been a feature in tackling work-related temperature exposure. Broadly, this equipment – more industrial than medical – collates data on the amount

of heat certain apparatus and machinery emits, ambient humidity levels, and whether protective screens, fans or extractors can alleviate air temperature and keep body temperatures at a comfortable level.

‘Fatigue, decreased performance, increased mistakes and accidents can all be started with just a 2% to 3% loss in body fluid,’ Dr Ross Di Corleto, a leading authority on the impact of heat in the workplace, says. ‘While limiting work to suit the environment is one approach, modifying the environment to suit work is the only meaningful solution, because it reduces reliance on human behaviour.’

Typical technology being used include devices that record the WBGT (wet-bulb globe temperature) – a type of ‘apparent’ temperature used to estimate the effect of temperature, humidity, air movement and visible and infrared radiation.

One study showed that even with an average WBGT of 28.5°C, 78.4% of underground miners and 69.6% of open-cut miners at North Mara Gold Mine in Tanzania were suffering moderate heat illness, with 80% having core body temperatures above the ISO 7933 threshold of 38.0°C for safety.

When thermal detection is introduced, however, improvements can be rapid. Thermal work limit monitoring was introduced in Australia in the late 1990s and in the mining sector annual hours lost due to serious heat illness fell from 12 million to six million, and the amount lost due to all heat illness incidences fell from 31 million to 18 million.

TECH SOLUTIONS

Wearable technology – on-body devices recording heart rate, body temperature and respiration rate – all add to a more detailed picture employers can create for individual employees. These can be used in conjunction with emerging ‘thermal risk’ phone apps.

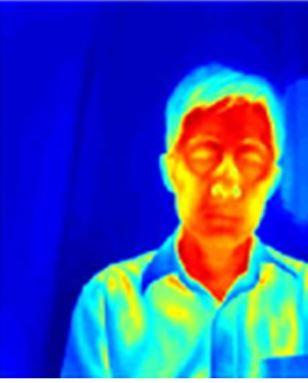

Technology initially developed to glean air temperature is now being fine-tuned by providers to be at the forefront of identifying tiny elevations in core body temperature – ones that could indicate fevers or COVID-19.

‘For those who have to work in offices or on-site, COVID-related thermal detection technology is a hugely exciting growth area that could be instrumental in helping employers give staff the confidence to reopen their offices,’ says Mary Ogungbeje, OSH research manager at IOSH.

The technology available includes non-contact infrared thermometers, thermal cameras and even full body scanners. All typically work to an accuracy of +/-0.3°C and providers say they can be indicative of illness, suggesting staff don’t enter the building until they take a full COVID-19 test.

A GROWING MARKET

Appetite for what the technology can do has seen demand boom. The global thermal imaging market size was worth $2.27bn in 2019 but research firm Yole Développement predicts that thermal imaging will be a $7.6bn market this year.

Mary accepts it brings vital confidence to employees around the health and safety of their work environment, but warns: ‘Technology should be seen as part, but not all, of a risk assessment.’

Some products, which attempt to bridge the divide between being industrial and medical equipment, still have doubters. Some measure skin temperature (rather than core temperature), causing a debate about whether natural skin fluctuations coming from cold outside air could impact results, or whether equipment positioning could also give bad readings.

In July 2020, the UK government said temperature screening products were not ‘a reliable way to detect if people have a virus’. Graeme Tunbridge, director of devices at the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency, said: ‘Many thermal cameras and temperature screening products were originally designed for non-medical purposes. Using these products for temperature screening could put people’s health at risk.’

Naturally, providers want to push back on this. In December, Tevano launched its ‘Health Shield’ temperature-tracking kiosk. Its CEO, David Bajwa, says: ‘It reads face temperatures, and the technology can distinguish between sudden changes in thermal readings that might occur because someone has come from a cold to a warm area, or even that they may be hot, because they’ve rushed to work, and are cooling down.’

Despite the conjecture, however, businesses are opting to go ahead. Last summer, Network Rail worked with Thales Group to roll out thermal cameras measuring the temperature of its staff at 108 critical sites across the UK. Rishi Lodhia, EMEA managing director at surveillance products company Eagle Eye Networks, says: ‘The benefit of video cameras with thermal detection technology is that it eliminates proximity challenges. The footage is obtained from a safe distance without an employee needing to be on-site, and the results are analysed and documented by the system.’

GLOBAL WORKPLACE TEMPERATURE LIMITS

UK: No maximum limit. Minimum of 13°C to 16°C.

Spain: Temperature for sedentary work must be between 17°C and 27°C, 14°C and 25°C for light physical work.

Germany: Maximum of 26°C in a workplace unless it’s hotter outside.

China: Outdoor work must be suspended at 40°C.

DETECTION AND DATA

Other technology can be used to alleviate fears about where devices are positioned. ‘A thermal calibration unit is a device that maintains a specific temperature and doesn’t reflect any energy from its surroundings,’ Rishi adds. ‘It’s used as a constant point of reference for the thermal camera – so if a warehouse entry point is particularly cold or windy, for example, the readings aren’t affected.’

One factor that cannot be ignored, however, is that the technology also brings about data collection concerns. ‘Organisations will clearly have to consider country legislation around collection and storage of data, permissions from employees to collect it, and on what it may be used for,’ Douglas says.

It’s clear to see that thermal detection – whether to prevent employees overheating and causing heat-stress related accidents, or identify illnesses employees are potentially carrying – is now much more in people’s consciousness. While there are still fears of false positives and a necessity to create employee buy-in, the case for the need for more detection is clear.

Source – IOSH